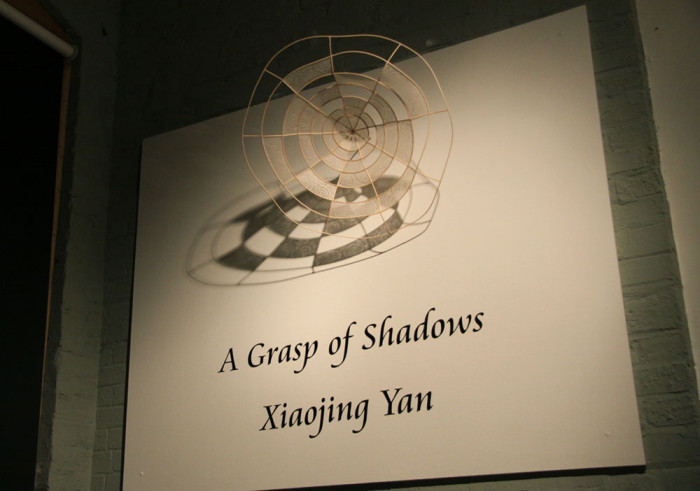

A Grasp of Shadows

Here at the intersection of Richmond Street and Spadina Avenue, taking in the art of Xiaojing Yan, one might naturally consider the proximity, only a few blocks away, to the heart of Toronto’s old Chinatown. Or sense the cultural strands extending from lately established, populous, prospering Chinese suburbs, such as in Markham, where Yan resides. Or ascertain a nurturing umbilicus that fortifies recent emigrants from the Chinese motherland, as again applies to Yan, who came to Canada from the city of Nanjing in 2001. The further out one projects such associations, the more plausible and relevant the assumptions. However Yan really is expressing or yearning for an inward sense of place, primarily as an artist; she sustains and balances that artistic intention and focus along with more public and socially conditioned identities of being a woman, a new mother, a new Canadian, a single child whose parents remain in China.

Yan’s became an artist as a child who started to learn traditional painting at seven years old. Her parents encouraged, that is to say allowed, her to follow her apparent talent and joy. She owes them a lot. Chinese classical painting encompasses several aspects—tonal ink brushwork analogous to what in Western art is considered the domain of drawing; calligraphy too, therefore the fusion of word with image; restrained application of colour; disciplined, mindful technique; respect for tools and materials, for instance, paper; the scrutiny and contemplation of forms and motifs, so that sensitivity melds with tradition; repetition, in the form of practice, rehearsal, so that accomplished execution extends from experience, and in abstinence from singular representation, wherein the figure is always part of a larger pattern.

Yan is easily conversant with painting. As we discussed a title of her exhibition, she told me that “Lue ying describes sketching or glimpsing a scene or sensation in a poetic way; lue means seize, brush and glance; ying means shadow, reflection and image. A literal translation of lue ying would be ‘seize the shadow’ or ‘brushing past shadow.’” In response, I proposed that the verby noun grasp might be suitable because of its definitions, “1: clutch, seize, firmly grip; 2: mastery, control; 3: mental hold or understanding” applied particularly well to her.

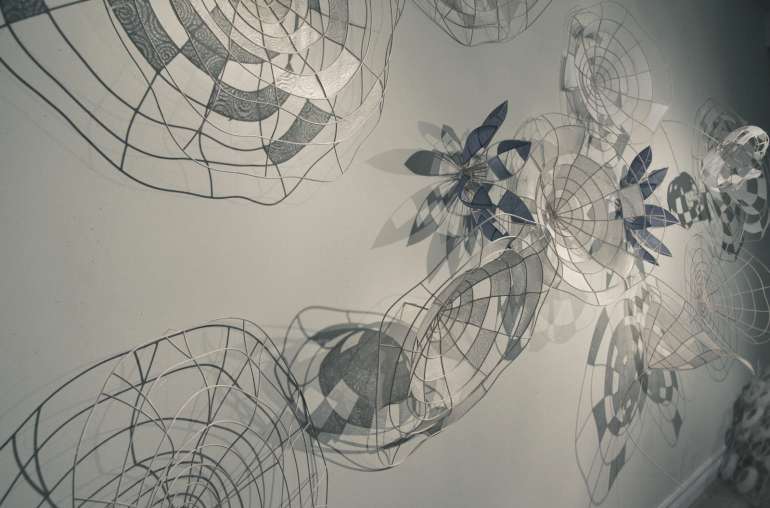

Yan has become a sculptor, maturing into an assured artist through a distinctive handling of materials, but her formation in painting has always remained apparent in that handling. The early material tests of the two installation works in this exhibition inspired our conversations about painting and my inquiry into its role in her growth. Specifically, In the Pond both by its structure and its motif. The radiating forms of multiple lotus leaves attained a watery, floating quality because of the shadows they cast on the wall behind them. Plus I was aware that lotus leaf images have been a mainstay of Chinese art since ancient times.

Yan told me that she concentrated on lotus paintings when she was younger. “I used to practice a lot in my teens. There are two types in style in general. One is called Gongbi. It’s more realistic and detailed. The other is Xieyi. It’s more abstract. I like the more abstract ones more. I feel they capture the essence with minimal effort.

“The Chinese have always loved lotus flower paintings. Lotuses are thought of as being like a gentleperson, who keeps clean and healthy in a dirty environment. Chinese poets use the lotus to inspire people to continue striving through difficulties and show their best part to the outside world, like the lotus flower that brings beauty and light from the darkness at the bottom of the pond.”

In the Pond is the title of the first novel by author Ha Jin, published in 1998. It is the story of a misguided artist in a small town in northern China during the transitional years following the death of Mao Zedong. The protagonist, Shao Bin, has an ordinary but unfulfilling job in the maintenance section of a factory. He uses his brush to protest against authority and perceived injustices. Shao’s caricatures and cartoons find unlikely attention in a bigger city and even the capital, Beijing, which partly insulates him from retribution by his superiors. That and his undeniable talent, such as is only beginning to gain social acceptance and even value at the end of the Cultural Revolution. At the end, Shao attains a more prestigious position as a local propaganda officer, but his newly gained, accidentally won stature requires that he stay in the same small provincial pond and will fail to fulfill him as an artistic. Yet he has nonetheless flowered in a dirty environment. One of the interesting characteristics of Ha Jin’s book is that its style and metaphors themselves adhere to the strong shadows of the Chinese painting tradition.

Literature is not the only the only Chinese art form to pay deferent homage to painting. Yan and I also looked at performances conducted by composer Tan Dun, his Water Concerto and Paper Concerto that centre on these essential elements of Chinese culture. Dun turns these substances into sonic material from which music is sculpted, spatialized and ultimately made visual. Having seen Tan Dun lead an orchestra in these concertos stirs my imagination as to how richly activating Yan’s lotus-leaf-and-flower installation will turn out.

Star Mountain straightforwardly names of the image and the material from which it has been created, star anise pods. Pinned to the wall, they create a more subtle shadow effect from small, desiccated organic units, some whole, some broken. They articulate the stuttered ridgelines and clefts of old, weathered, mainly barren mountains. However the fragmented contours also suggest silhouettes—trees, creatures, people perhaps—that cling to this forbidding outcropping, shadows that are signs of life—small singular lives that exist without recognition or effect on the relentlessly turning world.

Ben Portis is the curator of the MacLaren Art Centre in Barrie.